From a dictatorship to the European Union

In 1939, the Spanish Civil War was over. The rebel side won and transformed the Spanish Republic into a dictatorship and Francisco Franco, who lead the military uprising, became the dictator.

The first decades were a stage of famine and poverty: the government tried to create a self-efficient country with very strong border control. The lack of international commerce in a country destroyed by a Civil War created a situation where hunger and rationing were the typical dish. This situation let no other option to Franco that opening the borders and the economy, and that is the point where the Spanish growth began.

In 1975, Franco passed away and Spain became a democracy. Spanish economy kept growing due to the international commerce, tourism and the entrance into the European Union. Since 1984, Spain was living a stage of enormous growth. Its GDP was growing at incredible rates, way higher than the rest of developed countries. The famine lived during the decades after the Civil War looked very far away, now we were rich!

Global crisis and the effect in Spain

In 2006, the crisis in real state hit the US but it was not until 2008 when it arrived in Spain. As I’ve said, Spain was living some decades of incredible growth, the problem is that the Spanish economy was highly dependent on real state and the Spanish private and public sectors had extremely high debt rates. Reality hit Spanish economy and what seemed a rich country started the greatest crisis of its modern history.

On May the 15th 2011, a social movement called 15M (named after the day when it occurred) appeared and thousands of Spanish citizens took the main streets of the biggest cities to show the discontent with the political leaders. The protestors where called “outraged” and wanted to complain against the political privileges, corruption, cuts in public services, unemployment, etc.

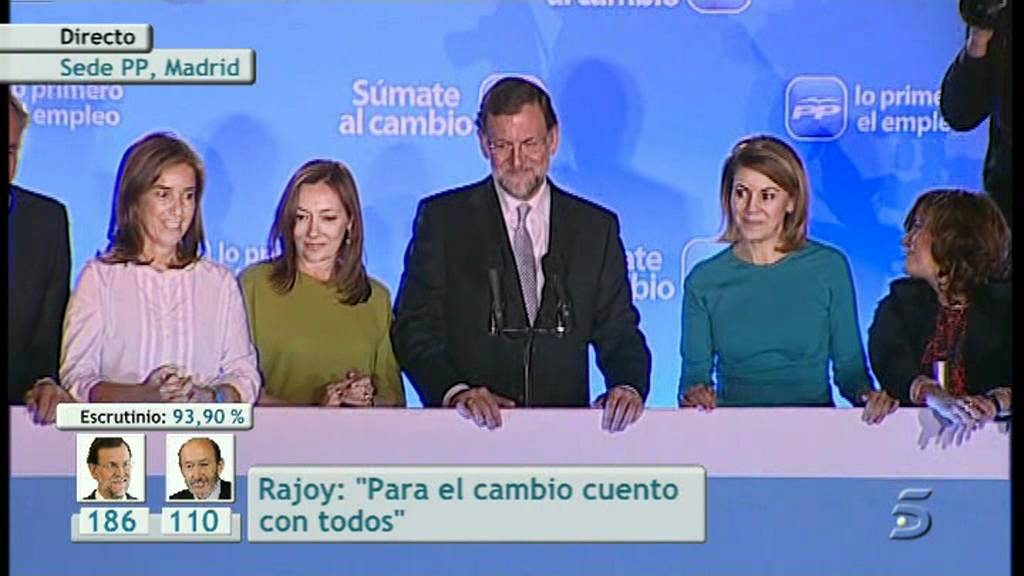

The situation was so terrible that the leader of the PSOE (center-left party) and President of Spain called for elections one year before his mandate expired. The result was an easy absolute majority for the PP (center-right party).

The new government and the recovery from the crisis

During campaign, PP promised to reduce taxes but after the elections, they did the exact opposite. The goals that the EU set to the new government were to reduce the public deficit and to increase the Spanish productivity.

To do so, Mariano Rajoy (the new President) and his party made cuts in the different public sectors, increased the taxes to collect more money and created new labor laws that permitted companies to fire workers in a cheaper way.

The first two measures stopped the increase in the Spanish debt (which had already overcome the 100% of the GDP). The third one allowed the companies whose sales had decreased to fire the employees that they didn’t need any more to decrease their costs and be able to survive to the crisis.

All these measures carried out by the government helped the Spanish economy. Maybe better measures would have meant a faster and bigger recovery, but at least during this mandate the economy had some recovery. The problem is that the working class barely felt this recovery: unemployment rates were still close to 25%, workers feared to be fired (which, in part, was a reason for the increase in the efficiency in the Spanish market) and, while families were evicted from their houses for not paying their loans, the Spanish government rescued the banking sector with public funds. All this tension caused that the 15M moved from the street protests to the Spanish urns. For the next elections, two new parties were born and the Spanish bipartidism was over. But that will be explain on our next post.

Me encanta la idea de hacer un blog sobre la situación política actual española, es muy interesante. No hay excusa,…

I liked the blog, very useful and well done.

Amazing photos!! Thanks, it’s very interesting!!!

Nice blog! I think you didn’t have to explain so back in time but for the rest it was really…